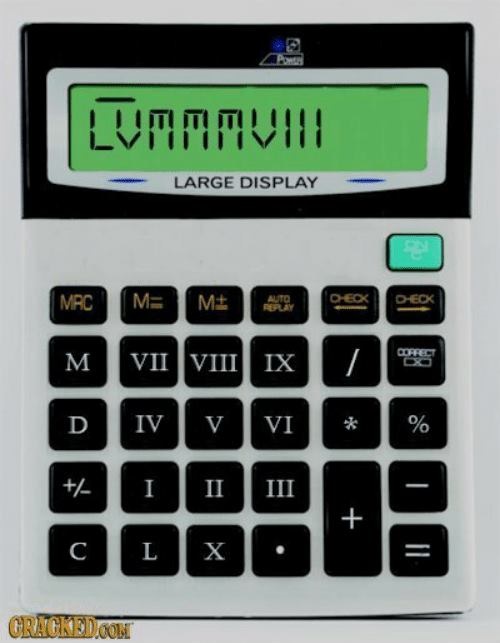

While digging around my hard-drive, I found this old meme someone sent me ages ago. Naturally, I wanted to share the chuckles with you, my loyal Felix fans!

But with my son learning about Roman numerals and me editing In Victrix (and making sure chapter numbers are correct), I thought it a great opportunity to delve into the history and usage of this system.

So buckle up! I assume you’re familiar with the basics, but this is going to be a deep rabbit hole.

The Writing and Origin of Numbers

Roman numerals involve representing numbers with letters, same as many other systems at the time (like the Greek and Etruscan). Originally I noted one, V for 5, and X for 10. Two theories have been proposed for their origins, based on simple counting (imagine a shepherd counting sheep in the field, rather than in bed).

Notches: on a stick, one straight notch per sheep. Two notches in V for 5 and then two crossed ones – X – for 10.

Fingers: one finger per item, with the thumb perpendicular for 5 making a sort of V. Cross the thumbs for two hands as an X for 10.

These don’t go far, but form the basis. The Romans got their system from the Etruscans, who used 𐌠, 𐌡, 𐌢, 𐌣, and 𐌟 for 1, 5, 10, 50, and 100 respectively. The Romans inverted the 5 and 50 at some point, and then the ↆ got flattened to an upside-down T (⊥) and then an L.

In comparison, the Greek method used more letters — one each for 1-9, then a letter for 10-90, and 100-900 — adding more symbols and diacritics for larger numbers. This required many more symbols, but made but made written numbers more concise. Besides, Greek cared more for geometry.

The Etruscan 𐌟 for 100 was written as ↃIC, which then devolved to just Ↄ or C, with C eventually winning most likely due to the correlation to the Latin word for one hundred: centum.

Two methods were used for larger numbers. First was apostrophus which consisted of adding the same kind “parentheses” around I: 500 is written as IↃ, while 1,000 is written as CIↃ. This is probably due to Greek numbers using Φ for 500. The Romans used it for one thousand and rendered it as CIↃ, and 500 was half that so just the IↃ. This became D for 500, and CIↃ visually became M — again probably due to similarity with the Latin word mille for one thousand.

More parentheses could be added for higher orders, but that was cumbersome. A different method called vinculum was invented. To get into higher numbers, add a line above a symbol to multiply it by 1,000.

Around the 6th century CE, some mathematical works show the worn nullus (nothing) for zero. By 725, Bede was using N for zero. Hindu-Arabic decimals was introduced 13th century, notably in the Liber Abaci by Leonardo Fibonacci.

This is probably stuff you mostly now from the modern usage of Roman numerals, but still begs the question how the heck did they perform any calculations with this unwieldy system?

Arithmetic

You probably know that numerals can be added. I is one, II is two, III is three. You’re probably know that IV is 4, V is 5, and VI is 6. But this notation — subtractive — was used in parallel with the additive notation: IIII for four, and VIIII for 9 (instead of IX). But you can only subtract something that is no more than 10 times smaller. So 99 can’t be written as IC, but has to be written as XCIX, which is (100-10)+(10-1).

The consistent forms over time were 4 (IV), 9 (IX), 40 (XL), 90 (XC), 400 (CD) and 900 (CM). But as for everything with three millennia of history, their usage was inconsistent and fraught with exceptions and changes over time. On the Coliseum, for example, gate number 44 is marked as XLIIII, and not XLIV. Or funeral stele showing IIX for 8 or XIIX for 18 (which is closer to the Etruscan way, but still occasionally used well into Empire times). Not to be confused with the 22 legion, which noted itself as IIXX…

Hilarity ensued. This confused not just modern students, but the ancients themselves. When it comes to arithmetic, subtractive notation, while concise, is annoying. The solution was often to first change it to additive notation and then do the calculations. Which brings us how to do calculations.

Addition

Addition is simple. Change everything to additive notation, add all the numbers, reduce multiple of the same letter to a higher order, and then change back to subtractive if desired. For example 99 + 49 is XCIC + IL, which is LXXXXVIIII + XXXXVIIII, which if we just sort everything we get LXXXXXXXXVVIIIIIIII. This is easy to group and translate to (LXXXXX)+(XXX)+(VV)+(IIIIIIII) or CXXXXVIII for 148 (additive notation). Easy peasy.

Note from the 99 example above (XCIX) that things are more or less positional. So we separate and add as we’d do adding a column of decimals. More or less.

Subtraction

Subtraction is only slightly harder. Same as before translate to additive notation. Then eliminate all similar letters. Then just expand values and subtract as needed.

For example 123 minus 39. That’s CXXIII – XXXVIIII. Eliminating common letters we’re left with C – XVI, or LXXXXVIIIII (changing 100 to 50+40+5+5, all in one step) minus XVI, which leaves us with LXXXIIII, or 84.

Multiplication

Multiplication is harder. It’s based on a series of halving and doubling numbers. Halving is easy: just pay attention to the V’s and I’s, but halve the others. eg 127 is CXX II, so half each xould be L X III, with a remainder of I, or 63 (and one half). Doubling is just doubling the letters, and then grouping them.

To multiply two numbers, make a table with two columns, and enter the two numbers to be multiplied into the first row. Write the next row down by halving the first number (discarding remainders) and doubling the second. Continue until there is nothing left to halve. Discard all the rows where the left number is even. Add the remaining numbers in the right column.

The reason why this works has to do with binary arithmetic, and the mathematical proof for the method is a bit beyond my rusty college math skills.

Anyway, there you go! Easy, right? See here for a short example, and just imagine what is must have been like with large numbers.

Division

Division is even worse, and is akin to modern calculus integrals. You kinda squint at it and take shortcuts (like common denominators and repeat subtractions), until you get there.

Fractions

In the example of division above, I mentioned the one-half remainder. Romans used a 12-base system of fractions, as 12 is a pretty useful number. (Ancient Assyrians used base 60, so there’s that).

Basically it was a dot for 1/12, 2 dots for 2/12 etc, and S for half (semi). Then S with a dot for 7/12 etc.

So our 63 and a half would be written as LXIIIS.

(Just don’t confuse that sentence-end period after the S to mean a 7/12 fraction 😜)

There were other notations for more fractions and I’m sure that there were ways to calculate with them but there isn’t enough nurofen for both of us if we go there.

Calculators

To aid in doing complex calculations, the ancients used counting boards and later abaci. Counting boards are the simple version, a board with places to mark numbers with small stones, and an abacus uses two columns for each position to help break counting a lot of 1’s. They existed for millennia all over the place.

The Roman innovation was really a simplification. It wasn’t as sophisticated as earlier Babylonian ones, but was more portable and used based-10. Note the notations with “parentheses” for increasing numbers, and the bits on the side for fractions. It was certainly useful enough for all that tax collection and paying legionaries.

The word abacus means calculation (ref the Fibonacci’s Liber Abaci above) and is of uncertain origin, but the word calculation is derived from Latin’s calculi, the plural of calx — a pebble, or small gravel stone.

BONUS! Why do some clocks use IIII instead of IV?

Congratulations on making it down so far! You deserve some FUN FACTS as a Parthian-shot of entertainment.

You might have noticed some Roman-numeral clocks rendering 4 as IIII instead of IV. You might have thought that’s odd, or wrong, or lazy. But it actually has a long history, as long as clocks themselves.

There have been several explanation purported, as there is no definitive answer. Some don’t strike me as particularly reasonable we we’ll skip them, but let’s consider the better ones.

First, as you’ve seen above, IIII is a perfectly valid way to write 4 which was used often enough. So it could be just what some clock-makers used.

When looking at the clock, the IIII balances better with the VIII on the other side, and generally making the clock look more symmetrical. This is still within reasons, but the explanation that I like the most is that it has to do with casting the numbers.

When you use IV for 4, and counting all the numbers on the clock face, you’d use 17 I’s and 5 V’s (in addition to the X’s). But if you used IIII you’d need 20 I’s and 4 V’s, which would make the job of the person preparing all those bits easier.

That’s it for now! Hope I didn’t give you too big of an headache (if you want one, just go try division…). This is probably something that wouldn’t make it directly into Felix’s stories. I’ll just have him curse out loud for doing some math and carrying the I, but won’t inflict it on the readers. Or maybe there’ll be some cursed abacus, or we might delve into engineering practices and tools in general. The future will tell what evil tortures I can devise for him 😈

I hope you found the insights into Roman culture as fascinating as I do. I take great care to fit these nuggets of human life and drama into the stories I write. If you’ve read the novels, I’d love to hear from you!

If you haven’t yet, why not enjoy the free short stories and novels until next time?

Thanks for all that!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reminds me of this excellent paper by Stephen K. Stephenson, which explores the possibilities of the Roman hand abacus and the counting board: Ancient Computers

https://ethw.org/Ancient_Computers

He also has an accompanying video series:

LikeLiked by 1 person