In writing the Sydney Sandstone novella, the very first DI Jack Finkel case, I ended up doing a lot of procrastination research into the early history of the City of Sydney. In the process, I uncovered some amazing material, which I thought I’d share with you here. This is both about the beautiful historical nuggets you can find online, as well as the way the mind of author works.

We’ll cover the ghost, the street corner, and the wonderful watercolours I have encountered (some in person 👻).

Note: contains some mild spoilers, so you may want to read the full story first!

The Need

Following the success of It Takes A Village, we at Purple Toga decided to collect more such themed anthologies. First cab off the rank, Rainbows aren’t just for Leprechauns. (Note to self: placeholder joke names end up living forever).

This one was themed around colours — the variety and significance to the human experience. At the time I was (still am 😅) prepping the first full-length DI Jack Finkel novel, “tentatively” titled Small Town Djinn (we all know it’ll go to press with that name). Since I knew that Jack started his policing career in Sydney and this would be his move to Tassie, I took this as an exercise in getting to know him a bit better by writing a case for him back in Sydney.

Once done, of course, this ended up as the case that got him sent down to Tassie… But I digress. I wanted a colour uniquely Sydney-ish, and what better than the amazing sandstone you see on old colonial buildings. I worked at the city centre for years, and took many a lunch time walk to feel the fresh air and admire the architecture. The locally quarried sandstone that one sees on public edifices is so quintessentially Sydney to me.

The Ghost

Since Jack deals with “unusual” crimes, I chose to look at some of Sydney’s ghost stories. There are, as you can imagine quite a bit that survive from the 19th century, that hotbed of superstition and nascent science! (with the exclamation mark, not to be confused with actual modern science).

While digging around, I find the following sentence about Pottinger St:

In 1831 the body of a woman was found in well in Pottinger Street in a most decayed state.

I was hooked! This was followed by a description of the inquest that followed (19th century colonial legal proceedings, for those not in the know, were usually help at the nearest pub). This includes how her husband, John Walker, identified her remains by the shoes she was wearing. The story ended with:

Since the disappearance of Anne Walker and the finding of the woman’s body in the well there have been many reported sightings of the a ghost at the well site, which is near the Parbury Ruins. The description of the ghost – a woman wearing a long dark cloak-like dress with a black bonnet – is almost the exact description of Ann Walker given at the inquest.

Right. So I have a ghost, a juicy murder, and a rough location. Sadly, when I tried to dig up more details about Anne of Pottinger Street, I came up blank. I could not find any more details, no accounts of her murder inquest or tales ghostly appearances. Not entirely surprising, given the very early days of the colony, but still.

Since her body was found in a well and there was an archaeological dig at what was the top of Pottinger St that uncovered the remain of an old cottage, two outbuildings, and a well. Since there are records of who owned that cottage, including it changing hands in the same year as her murder, I decided the coincidence is just too juicy and that would be her murder scene.

I then went digging about all the people mentioned — Anne Walker, her husband John Walker, and the two owners of the cottage on Pottinger St. One of the most annoying things is that you can find problems in each version of a story due to the changes in the city as well twists in recollections at re-tellings. For example, the inquest into Anne’s death was held at a “Red Bull Tavern” (good luck searching the web for that), but there is none mentioned in the area (the records show one further away). Did it exist, and like the Whaler’s Arms (see below) ceased to be referenced after a time, or is it a red herring? (Pub-pun intended).

I spent much time looking at old convict records, and the main thing I learnt is that about nine out of every five convicts were named either John Walker or Ann Walker. On the other hand, I think I found the right John and Anne Eliza Walker, and their family histories. Actually, I spent a lot of time to find them… You may call it procrastination (and there’s truth to that), but some of this little trivia made it to the very ending of the story for the emotionally-satisfying denouement, the family lines mattering for the catharsis, so you can’t say it’s time wasted.

In my quest of digging up old dirt, though, I unearthed some wonderful other trivia. This is better explained when we look at the area (literally a street corner) where the story takes place.

The Locale

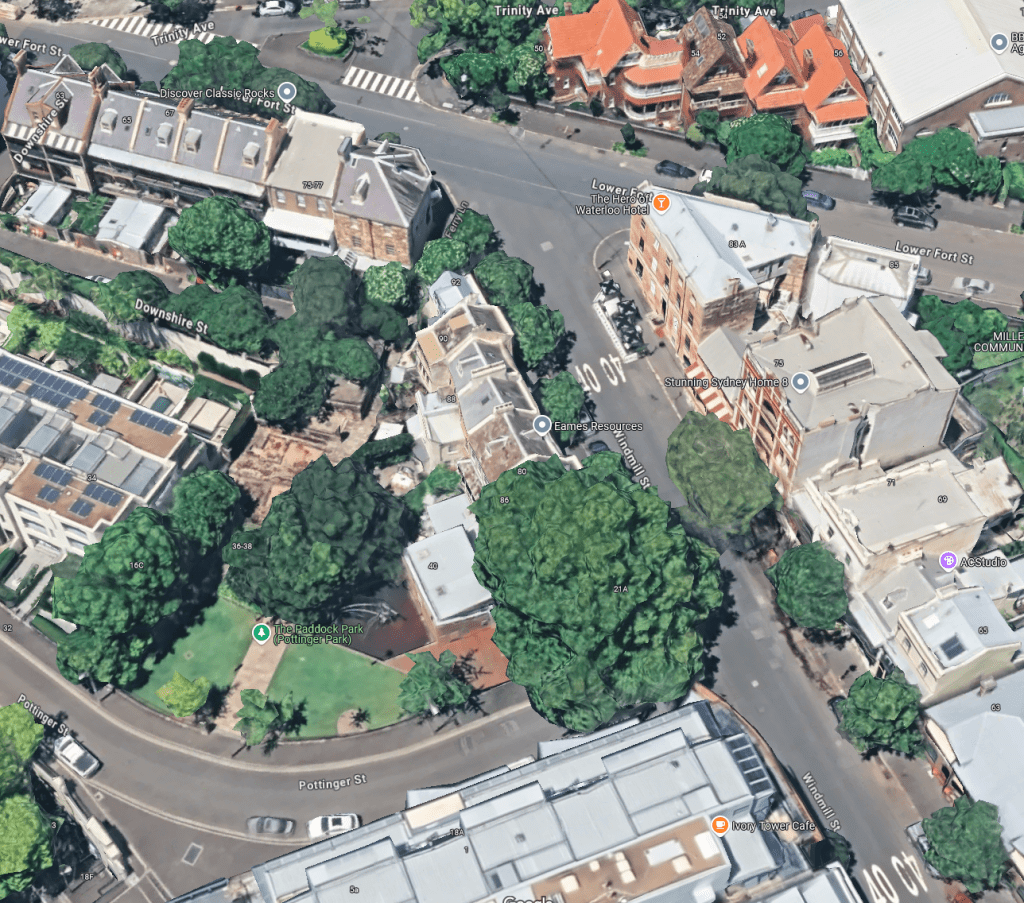

See this little park in the middle? My office was about 15 minutes walk away, so I passed there often. It’s a charming, hidden little gem in the old part of Sydney (Millers Point, next to The Rocks), a step away form the big smoke and noise.

What you’re looking at:

- The street at the top is Lower Fort Street, one of the oldest in Sydney. The one going down to the right is Windmill Street (there were three windmills along it), and the one curving on the bottom centre-left is Pottinger St.

- The small part is called ‘The Paddock.’ It used to be buildings early on, then when the area was demolished at the turn of the century (more on that below) it was kept as a park for children to play in, and still has a playground.

- You can see some ruins at the back. These are the foundations of two houses in ‘Ferry Lane’ — the narrow lane that goes from the intersection above and is now a footpath. The buildings in the area date anywhere from the 1830’s the early 2000’s.

- Pottinger St is curving now, but it didn’t use to. Both it and the lane used to run down to the water (bellow the bottom of the picture). When the foreshore was completely rebuilt in the early 20th century, things shifted around.

- At the intersection at the top are two very old and iconic buildings. The one on the right is the Hero of Waterloo hotel. (Which has its own ghost named Anne, who’s unrelated).

- On the left is the old Whaler’s Arms hotel. If you try to google it you’ll only find references to that name in Glouscester St on the other side of Sydney. In old drawings and photos, however, the building is both very distinctive due to it’s unique shape and has “Whaler’s Arms” writ large on the walls. It was restored some years ago to a fancy private residence (see pictures).

Easter Egg alert! The company that restored it is called GartnerRose, and has a partner called Witham. This will make sense when you read the story 😉

Those two buildings can be seen (looking from the top of the above image down Windmill St on the right) in this 1842 drawing by John Rae — you can see (somewhat faintly) the written signs of Whaler’s Arm and the Hero of Waterloo.

The History

So much digging! Quite literally.

As mentioned, the area changed quite a bit. This can be seen in both maps and drawings from the period (examples below). Ann was murdered circa 1831, where the area was mostly mud and shacks. Millers Point was so named because that’s were the mill was — in fact, Pottinger runs from Windmill St (guess why) down to the water.

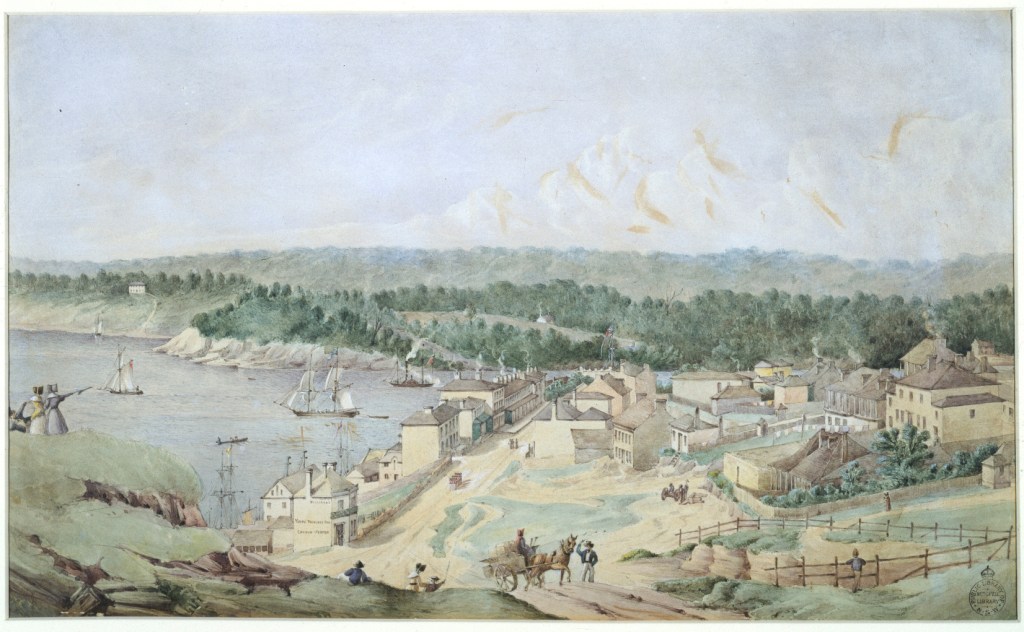

This drawing by the legendary Samuel Elyard is probably what the area looked like at the time. The collection is dated to the 1860’s, but the image itself is undated. It looks to me (having looked at a lot of other images) as the old Pottinger St Lane running down to the water from the corner with Ferry Lane — an area that no longer exists like this.

The Whaler’s Arms was established soon after, and the rival Hero of Waterloo circa 1842 (which still survives as a hotel, and I had the occasional beer there). Ferry Lane became a thing in 1848 when the ferry service across the Sydney Harbour began docking at Miller’s Point (which I think by then had gas works and commercial docks). The area filled up over the decades, and became quite dense, mostly housing dock workers (who notoriously only live in the best parts of towns).

Until Australia Day, 26th January 1900. That’s when there was an outbreak of Bubonic Plague in Sydney. The source was was isolated to the cesspit of no. 8 Ferry Lane, those ruins you see at the back of the park in the above Google Maps image.

It’s likely that rats carried the plague on board a ship, and then bit Arthur Payne who worked at the docks and lived at #8. All the Houses in the area were fumigated and then burned. The area stood vacant for a while, and then the NSW government resumed the foreshore (ie took ownership) and did major works. Part of them was the creation of Hickson Road, which necessitated cutting away parts of the hill and rerouting Pottinger St to have the current curve.

The area — including Walsh Bay, where the wharves are — was redeveloped again at the end of the 20th century. Times being more modern, there was an archaeological impact assessment, which actually served me as a good starting point (for the layout at least; they didn’t consider ghosts as impacting architecture, or vice versa).

For the purposes of the story, I have kept an old cottage from the 19th century on where is now the public park, which somehow survived the foreshore redevelopment. This is the scene of our little crime.

The Art

The above images are two of my favourites. You should see the rest of the Samuel Elyard collection — his watercolors are amazing! They capture the pastoral character of early colonial days.

Note: I’m ignoring the horrors of what was visited on the native inhabitants during this time. I acknowledge the traditional owners of the land, but I don’t feel comfortable telling their stories. It doesn’t serve the modern-day Jack mysteries, and I’d rather not commit cultural appropriation.

Another watercolour is by Joseph Fowles, from a slightly different angle. It shows the Whaler’s Arms in it’s original name of Young Princess Inn, and before the Hero of Waterloo was built:

Though this image is dated to circa 1845 in the collection, the fact that it doesn’t show the Hero of Waterloo (which John Rae above does show in 1842) means it’s probably some years older than that. It was fun (read: a headache) to do all these cross references and construct a timeline in my head. Considering Jack visits all these buildings during his case (well, he has a beer at the Hero of Waterloo hotel), I consider it time well spent. Besides, these were open in tabs while I was writing, to provide inspiration.

I also particularly love this 1890’s picture by Alfred Tischbauer:

Go an open it in a full-screen view. There’s something utterly magical in the grimy, grungy docks of the 19th century, with both steam and sail ships.

In particular, see the street running up on the right. That’s Pottinger St, connecting the wharves to Windmill St. The very top of the Hero of Waterloo hotel is seen a bit on the left at the top. (You may need to go to the source and zoom in).

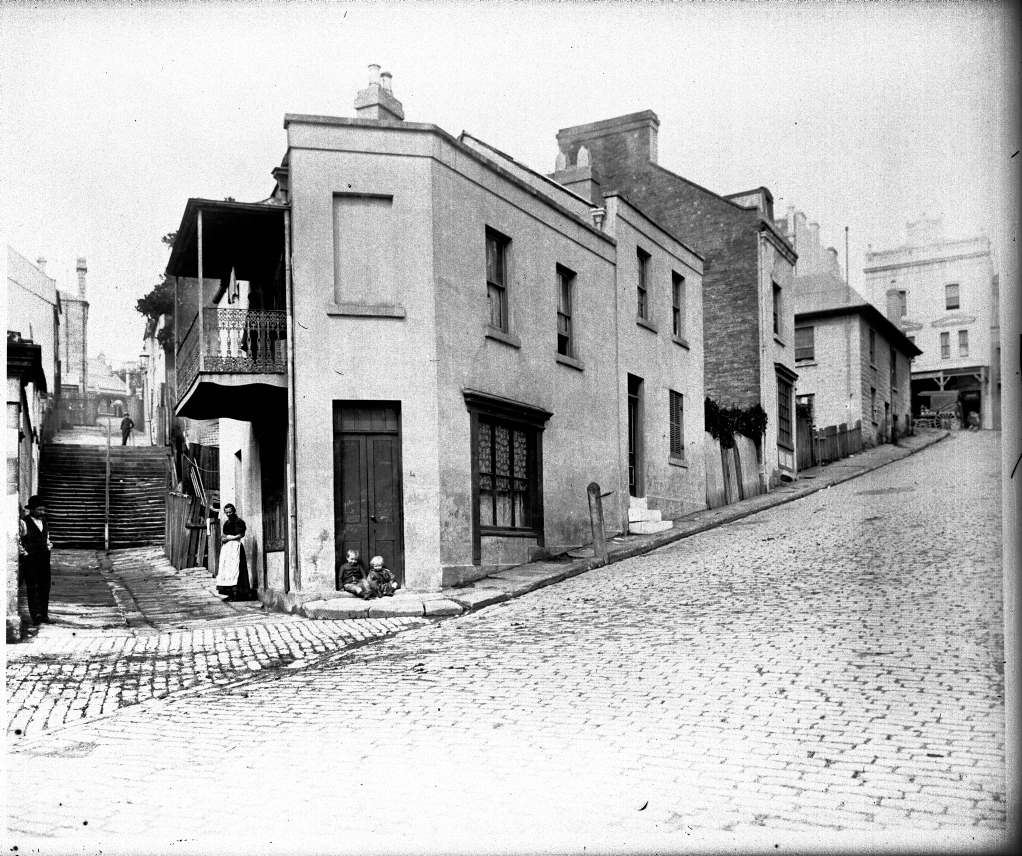

In the middle of Pottinger St, you’ll note the lane going right. That’s Ferry Lane. There’s a specifically funny shaped building on the corner:

If you go to Flickr, you’ll see some annotations that help identify it. The photograph is dated 1900, and according to this drawing from circa 1902, you can see the deterioration the years of the plague inflicted:

People are clearly still living there, though that white notice pasted next to the door looks suspiciously like a plague notice. In any case, this house no longer exists as it’s the public park where Pottinger St now curves. The street which starts in upper right in these images now goes to the middle left, in between the alley and the street. This is exactly where our story takes place! (Just outside the frame, dammit).

Anyway. I would have loved to get prints of those pictures — the John Rae, Samuel Elyard, and Alfred Tischbauer in particular — to hang around my study. Sometimes all the inspiration you need is a bit of colour of a building stone. The magic, of course, is in tying the ghost, the history, and the colour of Sydney sandstone into a modern-day police-procedural, with occult forensics and reality TV.

I hope you enjoyed this trip down the past. This is the kind of research I do for writing the Unusual Crimes Squad stories whenever there’s a bit of history (and when you’re dealing with ghosts, that’s quite often!)

Want more? what are you waiting for?

Still here? Fine, fine, here’s the obligatory post-credits scene.

Take a look at this 1901 photograph — which was taken not far from where our story takes place — as it has the most hilariously awkward photobomb description:

Eight children, one on a horse, pose in front of a rickety wooden picket fence, watched by a man in the doorway of a makeshift outhouse.

Yeah, don’t you want to come out of the dunny to find all the neighbourhood children on the doorstep posing for a passing photographer? 📷😵💫

Anyway, go read Rainbows aren’t just for Leprechauns or my other short stories!